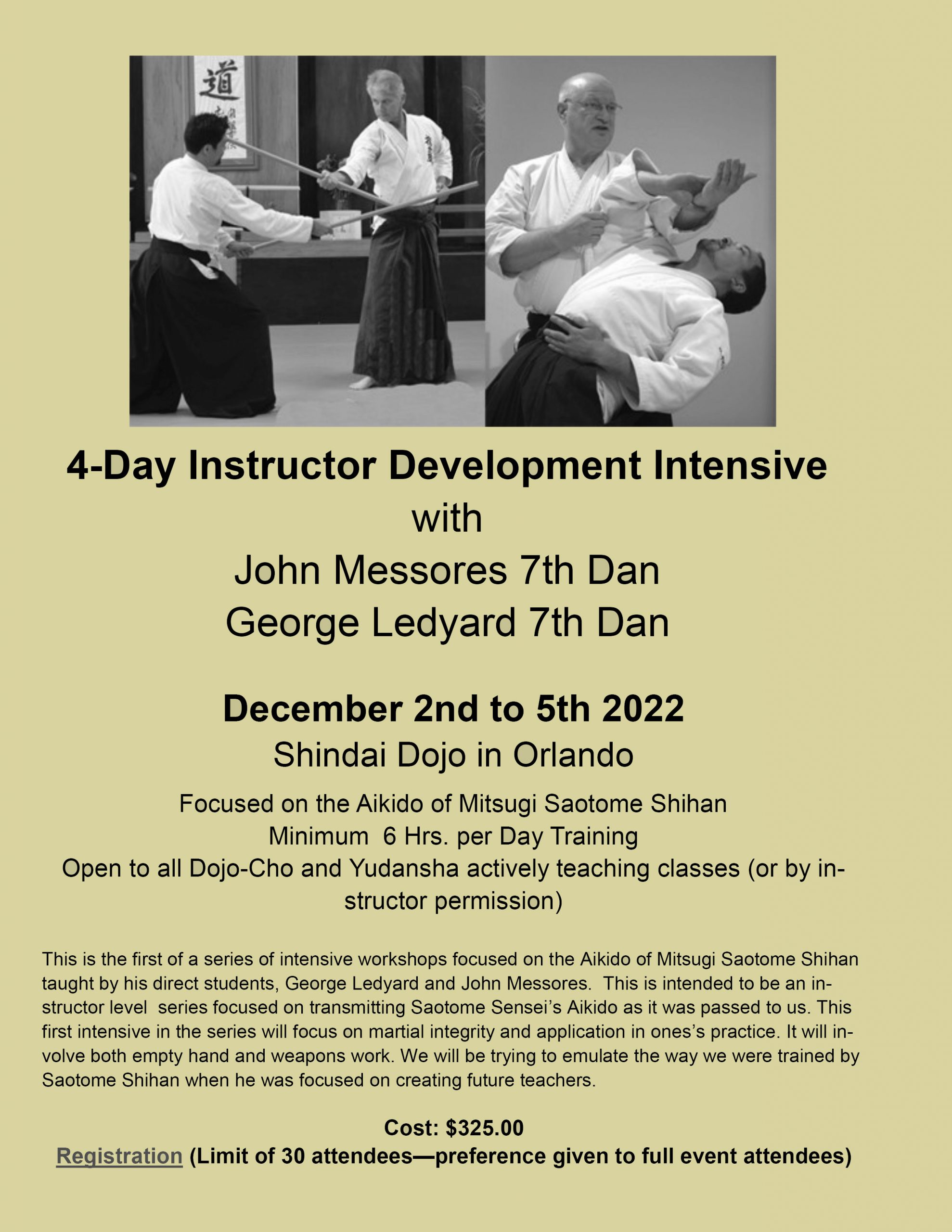

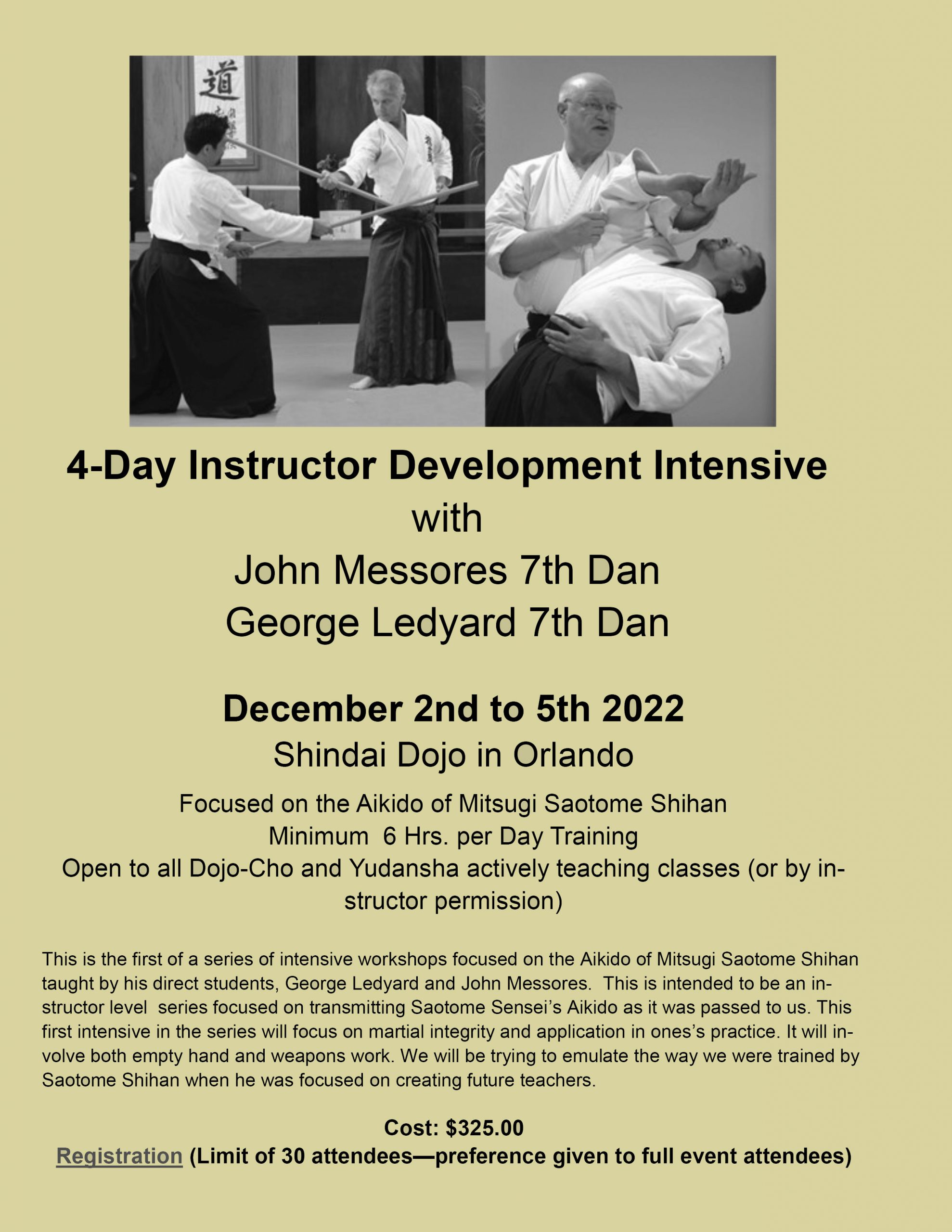

Shindai Dojo is pleased to be the first host for this significant event.

Offered by two of Saotome Sensei’s remaining primary students, this opportunity will provide insight into perspectives of Sensei’s teaching of Aikido as a “Martial Art”. The perspectives and experience of Sensei George Ledyard and Sensei John Messores will focus on current and potential ASU instructors to enhance for them a stronger foundation upon which to responsibly represent Saotome Sensei’s teaching. It will help our teachers present a greater breadth of Sensei’s teaching to our current and future students … that is the living legacy of his Aiki.

You can guarantee your registration for this event through Ledyard Sensei here:

https://events.eventzilla.net/e/instructor-development-w-messores–ledyard-senseis-2138577584

Why: I offer this excerpt from a piece written by Ledyard Sensei for your consideration. Are we what we think we are? What do we teach and provide?

Aikido practitioners can go on and on about the philosophy of Aikido. They will rhapsodize about how it has changed their lives and how it is a Budo, or Martial Way, a life Path or Michi. But if you look at the actual time and effort they put into their training, it is less than what would be expected of a kid on a high school athletic team. Does anyone actually think that junior is going to start in that game Saturday if he or she gets to practice two days a week?

Yet Aikido folks want to be validated and rewarded for putting in the level of effort that is convenient for them. They want the standards for the art adjusted to fit them rather than the traditional model in which one adjusted oneself to the art.

Essentially this all boils down to whether we decide to reward effort and participation or do we reward actual achievement? I am involved in discussions about standards and grading. In these discussions a common viewpoint suggests that focusing on quality, actual ability, and real achievement is somehow elitist. That we should be looking at all the wonderful characteristics of a practitioner, instructor, even more senior teacher as the basis for promotion rather than mere technical competence.

This has led us to a situation in which people get to senior grades merely because they have been around since the flood. That someone who does lots of good things for their dojo or organization can reach senior teaching ranks.

I think that we must decide to prioritize actual ability and technical achievement in moving people up the ranks. We must be looking at the transmission of the art as our first priority. It was communicated to me when I started training that, traditionally, your primary responsibility as a teacher was to create at least one, if not more, students who were as good or even better than you. Transmission was your job so that the art wouldn’t be lost.

Look around. Look at the first generation of American pioneer teachers. Have any of them produced a student or students who looks to be able to step into their shoes? I don’t see it. All the uchi deshi agreed that they had only each gotten a portion of what O-Sensei could do. As direct students of teachers who had been uchi deshi, I can say that we feel the same. So, if my generation of teachers can’t manage to replicate itself in another generation, Aikido devolves into a nice movement system and social club. It will lose what little martial integrity it has left.

Aikido has to reprioritize and make training competent, highly trained instructors the central focus. That means setting high standards, putting achievement ahead of effort and participation, and making the hard decisions about who reaches the top grades. And we have to stop thinking that focusing on quality is elitist and that everyone should be rewarded for participation like little kids. This is a martial art, a Budo. Mediocre teachers cannot produce excellence. That’s a fact. And without excellence this art dies.